Given how vast the tuning scene is in 2025, it’s hard to imagine a time when ordering aftermarket parts for your car wasn’t as simple as clicking a button.

This shift isn’t limited to the aftermarket world. Nearly every major auto manufacturer now offers a level of customisation beyond just optional extras – think BMW’s M Performance, Mercedes-Benz’s AMG Line, or Toyota’s GR series. In fact, today you can order an unpainted carbon fibre bonnet for your 2.5-tonne Range Rover Sport directly from Land Rover as an option if you’re so inclined. Whether that’s a good idea, however, is entirely up for debate.

Rewind a few years, and such behaviour from an OEM would be considered lunacy. But with so much demand out there – and manufacturers able to provide parts without voiding your warranty – it was only a matter of time before they wanted their slice of the tuning pie.

Now, let’s rewind even further, to a time long before magazines like Max Power and Super Street brought tuning culture to the masses. Depending on how deep your pockets were, your options involved having a bash at home or asking the local garage to help. But for those whose pockets were lined with serious cash – or better yet, oil wealth – there was another option.

How frustrating life must’ve been when not even Rolls-Royce or Bentley could offer a custom level of luxury for your car. The solution? Dial-a-coachbuilder.

Coachbuilding has a rich history, with the first examples dating back to the early 1900s. Alvis Cars, for instance, would provide a base chassis, which customers could then have customised with a completely bespoke body and interior. Think of it as an early form of flaunting wealth with your car, a one-of-one special edition with a price tag to match. But when everyone’s driving a one-of-one, the novelty wears off quickly.

The demand for such coachbuilt cars gradually fizzled out over time, especially during the two World Wars when many coachbuilders, like Alvis, switched to aircraft production among other things. Mass production became the norm during the Second Industrial Revolution and, as such, low-volume coachbuilding didn’t truly make a comeback until the 1970s and ’80s with a new wave of extravagant builds that catered to the ultra-wealthy.

Brands like ABC Exclusive, SGS Styling, Carat by Duchatelet, and Trasco were all heavy hitters during this era, becoming famous for taking requests that were anything but ordinary. This resulted in some of the most outlandish and wacky cars of the time – many of which rivalled those in the Sultan of Brunei’s legendary collection.

And it wasn’t just about styling. In-car entertainment was a major focus, with companies like Trasco fitting CRT screens and multi-deck audio systems into their bespoke builds. The idea was simple: Add more bling – more crystal, more leather, more opulence – than anyone else to make your build the most radical and expensive possible. It might sound vulgar, but when your clientele includes royal families, oil barons, and arms dealers, it starts to make sense.

In recent years, this period has come to be known as the ‘1000 SEL’ era, a term popularised by Bram Corts’ brilliant website, 1000sel.com, which meticulously covers the history of those key brands and coachbuilders along with the various special edition vehicles.

Why 1000 SEL? One of the most popular premium cars of the time was the Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class. Known for its unparalleled engineering and luxury, the top-spec 500 SEL (and later 560 SEL) boasted a 5.0-litre V8 engine and an extended wheelbase.

According to Bram’s research, in the ’80s, a Middle Eastern customer reportedly ordered a heavily modified 500 SEL from SGS Styling in Germany. When the car was delivered, the customer told SGS boss Chris Hahn that his car was “twice as good as a regular 500 SEL,” and that he’d like to have a badge on the back to represent that. What’s twice a 500 SEL? A 1000 SEL of course.

Though it was never an official model designation, the 1000 SEL badge soon became a symbol of extreme modifications and opulence, especially in the Middle East, during the height of the oil boom. It was a sort of pre-social media flex – a way for wealthy car owners to compete in creating the most radical, and expensive, variants of luxury and sports cars.

The 1000 SEL era is far more complex than this very quick synopsis and I urge you to delve deep into Bram’s website – it’s so interesting to see what was being done between 1975 and 1995, and the extortionate cost associated with each car. Especially now considering these particular cars and styles are coming back into fashion once again.

But what makes these cars truly fascinating is the wealth and secrecy surrounding their buyers. Was it owned by a government official? How did a businessman find over US$250,000 to spec a 1000 SEL in 1985? With such limited history out there, trying to unravel a car’s past only adds an extra layer of intrigue.

One thing’s for certain, finding any of these cars in good condition is no easy task. Even period parts from brands like Carat by Duchatelet now cost thousands – assuming you can even find someone willing to sell them.

This is where Speedhunters regular Higuchi-san enters the picture. He’s an avid classic Benz enthusiast, whose car history includes a 2JZ-powered 450 SLC, several Tommykaira W124s, and even a custom S124 estate converted with 500 E parts. His latest project, however, is the culmination of decades of passion approached with a modern Japanese twist.

Mercedes never made a wagon variant of the W126, but Higuchi-san’s 500 TE is far from the first conversion. You can thank the 1000 SEL era for that, in particular, Zender who was an early pioneer of the ‘TE’ W126. Zender famously built several examples, including one with an SEC front end, much like Higuchi-san’s creation.

There’s no eBay search or AliExpress link to order W126 estate conversions, but fortunately for Higuchi-san, he didn’t have to start from scratch. Not that it made the level of work required any less.

“This particular car was owned by a famous Japanese comedian in 1990,” Higuchi-san explains. “He loved American cars and considered a Caprice wagon and also the S124 estate before deciding to make the S-Class wagon. In his eyes, a wagon that anyone could buy would be boring, so he wanted something bespoke.”

Styling Garage Japan, the now defunct coachbuilder behind the original project, was known for building some wild custom creations, including limousines and even a Z32 wagon.

Their work was highly regarded, and when Higuchi-san saw this particular W126 become available in 2020, he jumped at the chance to own it.

However, the wagon had seen better days. Abandoned for years, the paint was cracked, the frame was rusted, and the bodywork was damaged. Worst of all, the custom interior was completely pulled apart. With no replacement parts available, the only solution was to painstakingly recreate and restore. Two words that haemorrhage time and money like no others.

Condition aside, the 500 TE had all the parts required to restore it to its former glory. The bulk of the custom exterior trim was all intact; it was just a little tired-looking. When Styling Garage Japan built the wagon, they used the rear end of an S124. That makes it sound relatively straightforward until you learn that a W126 chassis is nearly 100mm wider than a W124. Every panel had to be cut, extended, reshaped, and welded back into place – hundreds of hours of labour. You can see why it helped to have oil wealth back in the day to fund such a habit.

What really makes this kind of conversion so tricky is getting all of the swage lines and trim from the W124 panels lined up with the W126. Smoothing everything out would have been quicker, but Higuchi-san was determined to keep the car looking as close to OEM as possible before adding his personal touches.

“When it was owned by the comedian, the original Anthracite Grey was repainted to Mercedes Blue Black Metallic, before then further being changed to a lighter blue,” added Higuchi-san. “Because the paint was so damaged, we stripped it all off and resprayed the entire shell Palladium Silver to give it a modern look while staying true to the original colour.”

Seeing as all the chrome trim and plastics around the windows were custom-made by Styling Garage Japan (not a single piece from the W124 lined up against the original saloon items), Higuchi-san had no choice but to powder coat the worn-out mouldings and polish the remaining trim.

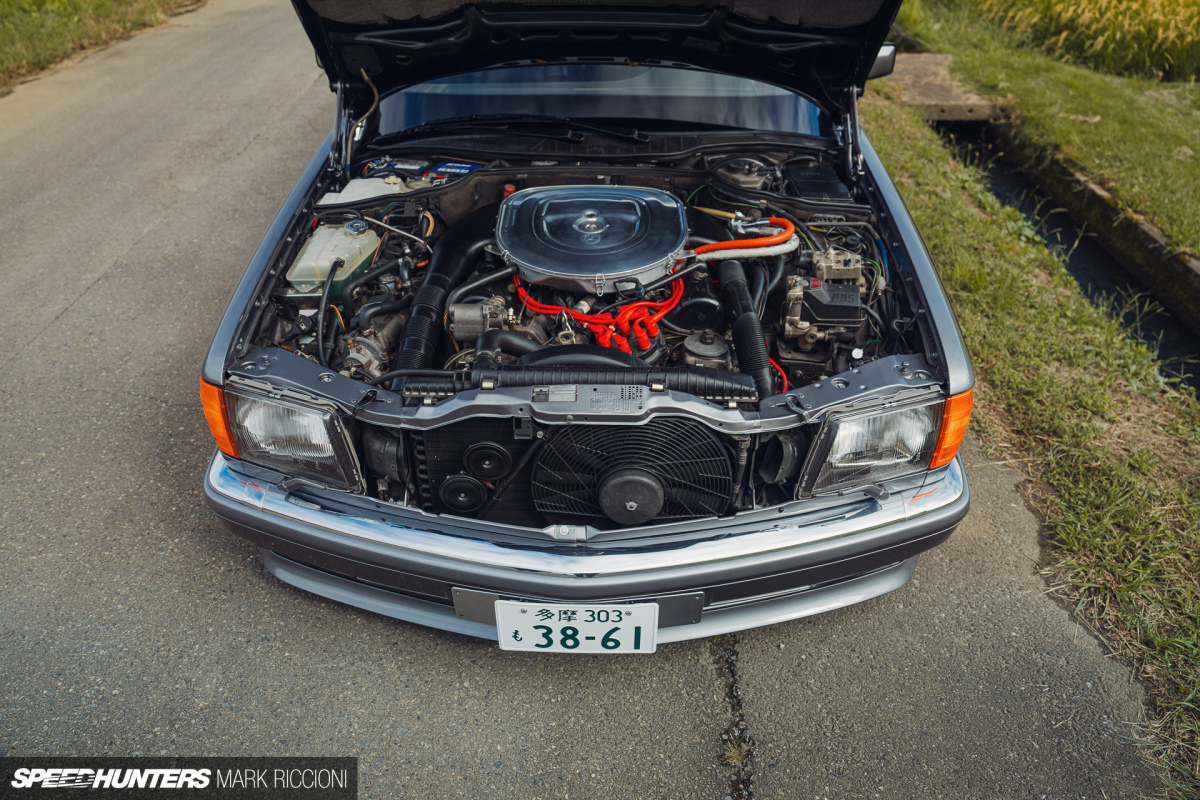

From the rear, you’d be forgiven for thinking it was just a widened S124 thanks to that angular boot and smaller rear lights. However, Higuchi-san wanted to retain the full functionality of the trunk, which meant building an entirely new custom floor panel and restoring all of the plastic trims used inside. Up front, much like Zender’s ’80s concept, a full SEC conversion was undertaken using all factory parts. Although less complex in comparison to the boot fabrication, to do it properly still requires both front wings, the bumper, headlights, grille, bonnet and slam panel.

Higuchi-san’s builds all follow a similar style in terms of the aftermarket parts he fits, the tell-tale sign being his own HWA Asteroid wheels. Measuring in at 17×8.5-inch ET18 and 17×9.5-inch ET17, the Asteroids are almost identical to the original Penta/AMG design bar one key fact: Higuchi-san makes his wheels in 17-inch size, while the original designs only ever existed in up to 16-inch.

Behind those wheels, you’ll find 6-piston ‘Brabus by Alcon’ brakes, which were first offered as a tuning upgrade for the W124 in the ‘90s. Aside from massively improving the stock brake system, they provide a subtle nod to the 1000 SEL era without overshadowing the rest of the car. The stance is enhanced by Dkubus coilovers, and genuine AMG W126 parts are scattered throughout, including the exhaust, steering wheel, and gauges.

It all gels together brilliantly. Higuchi-san has an annoying habit of building cars which seem to tick all the right boxes, and before you know it, you’re doom-scrolling through eBay preparing to embark on your own Benz build. But that’s a testament to his deep knowledge and passion for both his cars and the era they represent. In a world of quickly assembled builds that are promoted and phased out with dizzying speed, it’s always refreshing to see what Higuchi-san has up his sleeve.

“All in all, the project took three years to restore and complete,” he adds. “There’s still some more work to do, but such an interesting and unique car deserves to be restored properly. I do not build my cars for promotion or to sell, they are to drive and enjoy. I love the look of the estate, and many people cannot believe it was not a factory conversion.”

There are very few cars out there which don’t look better in wagon form, and I don’t ever remember driving a car and complaining that it had too much space. It’s why I’ll always be a massive advocate for any estate car; you get all the benefits of a good saloon with enough space in the back to bundle the whole family in. And Higuchi-san’s W126 500 TE is all the proof you’ll ever need that wagons make everything better.

Mark Riccioni

Instagram: mark_scenemedia

Twitter: markriccioni

mark@speedhunters.com